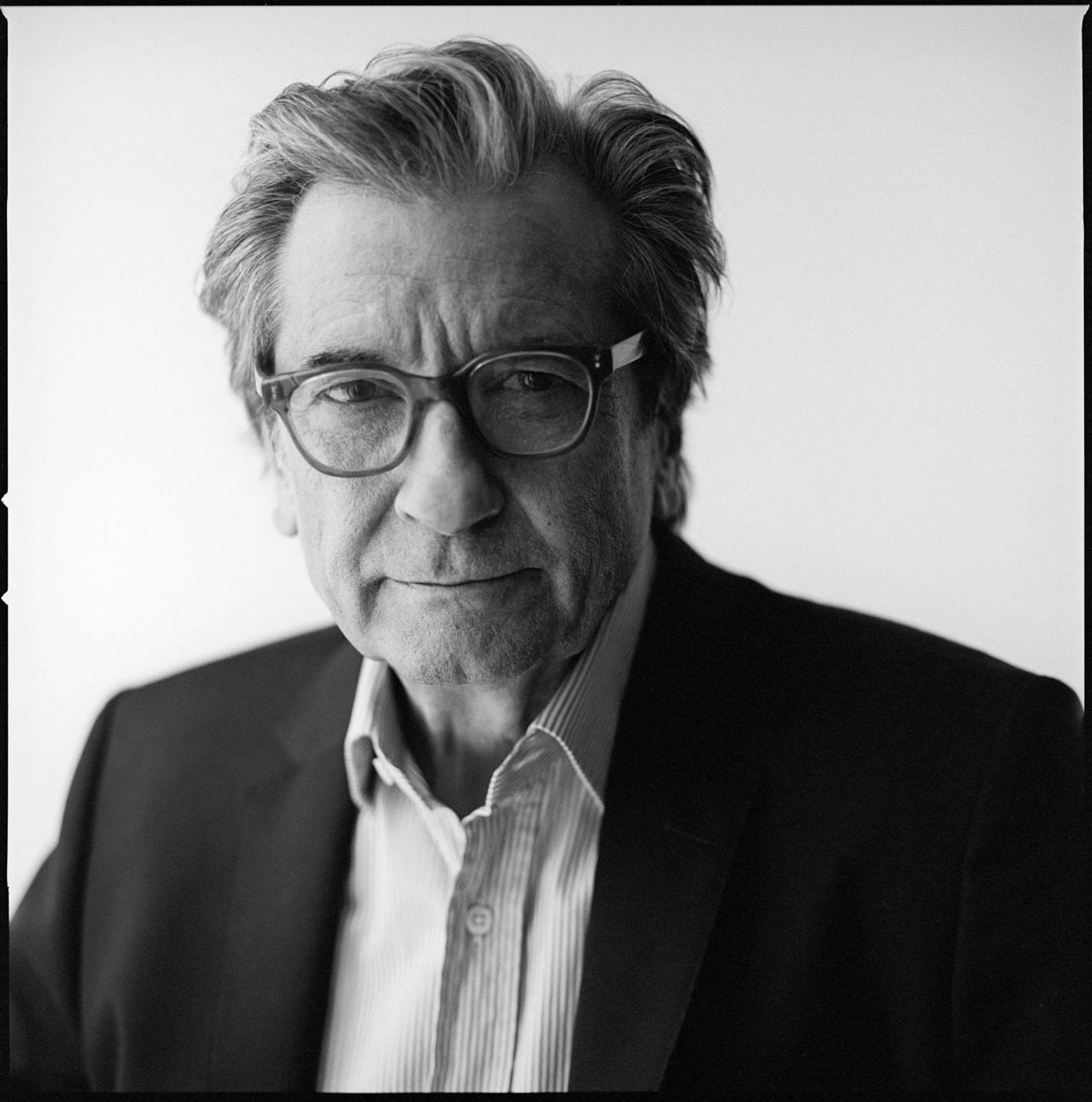

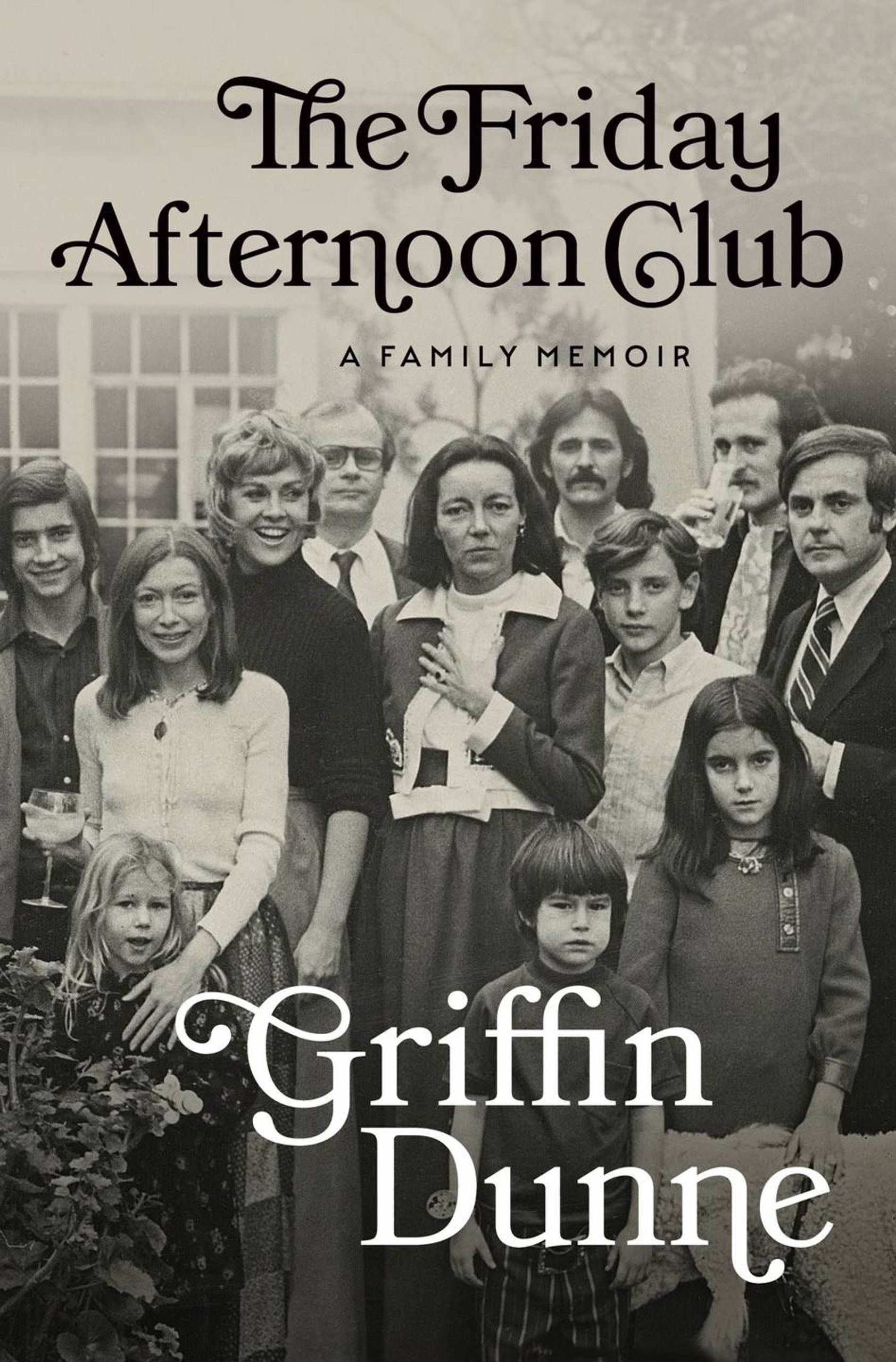

Griffin Dunne Reflects on Family, Fame and Friendships

The actor-producer-director discusses his new memoir, ‘The Friday Afternoon Club,’ and his remarkable lineage

Just a quick glimpse at the blurb for Griffin Dunne's new memoir, "The Friday Afternoon Club," makes it obvious that his life has been anything but ordinary. Casually sprinkled throughout the text are the names of some of the most notable individuals in the entertainment industry: Sean Connery, Janis Joplin, Tom Wolfe, Martin Scorsese and Carrie Fisher — not to mention his father, Dominick Dunne, his uncle, John Gregory Dunne, and his aunt, Joan Didion. Elizabeth Montgomery was his babysitter prior to finding stardom in "Bewitched." His childhood best friend was the son of actor Jack Palance.

In recalling a school father-son baseball game, he writes, "The dad who played Wilbur in 'Mister Ed' got most of the attention at the pitcher's mound for accidentally beaning the third-grade batter (whose father directed 'Green Acres') while the kid was taking a practice swing."

And yet, a deeper dive into the book reveals that it is so much more than a dishy celebrity tell-all. Despite having been raised among Hollywood and literary elite, Dunne, 68, is no stranger to hardship. He deftly intertwines lighthearted tales about his storied upbringing with candid accounts of relatable tragedies: his father's closeted sexuality, his brother's mental illness, his mother's multiple sclerosis, his own dyslexia, and the brutal murder of his sister, actress Dominique Dunne, in 1982. It's a beautifully written, poignant account of a family that managed to find joy, hope and humor in even the darkest of circumstances.

"The story of Tom Griffin's uncle dying in bed with his mistress, while his wife's in bed with the Admiral Bastedo — that's my favorite one. I just love that story so much."

Dunne, who can currently be seen on the Max series "The Girls on the Bus," recently spoke with Next Avenue about the writing of the book, his years-long friendship with Carrie Fisher, and the unexpected ways in which his sister's untimely death changed him.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Next Avenue: Many people have stories about that one family member who did something outrageous, but you have generations of relatives who had wild affairs and scandals. What was the research process like for the earlier chapters in the book, when you describe your family history? Did you know a lot of these stories already?

Griffin Dunne: I grew up on the story of [my grandfather] Tom Griffin leaving his society wife on the altar and marrying my grandmother, who was also engaged to be married. That was always family lore. But I have an aunt named Sigrid in Nogales who is the historian of that side, so all of the information I got about the Sandovals [on my mother's side] — from their mining and property owning and then losing it during the Mexican Revolution — I got from her. The story of Tom Griffin's uncle dying in bed with his mistress, while his wife's in bed with the Admiral Bastedo — that's my favorite one. I just love that story so much.

You were raised around celebrities, and you have many great stories in the book about the many Hollywood A-listers who would attend your parents' parties. But you write, 'When I moved to New York, I never told my new friends any of this and found my privilege embarrassing and inexplicably shameful.' At what point did you let go of that and learn to embrace where you came from?

Not long ago. I'd say sometime during the transformation of my father's entire character, where he grew into himself in his fifties. But even then, he had a book called "The Way We Lived Then" that came out, and I was embarrassed by the book and of our [childhood] pictures, dressed in matching suits and all that. It went contrary to the narrative I'd given myself as a New York actor. But when he passed away, I inherited his scrapbooks and they're my most treasured possession. I look at them constantly. I think they're such an incredible record of both social history and Hollywood history between 1960 and 1966. I used to make fun of him for ironing invitations and thank you notes from Jane Fonda and all these different people, but I look at it now as a record. I'm very proud of it.

At some point I became fascinated by the world in which I was brought up in and had regrets that I was really too young to know who these people were. You know, I couldn't talk to Billy Wilder about "Some Like It Hot." There was an Englishman named Ivan Moffat, and he talked like this [mimics an upper-class British accent] and had cigarettes with ashes that would get long and get on his suit and he'd flick off. My brother and I used to make fun of him when we were little. I found out too late that in fact, a lot of the [WWII] photography that we see, he was with George Stevens filming that, and that he was George Stevens' aide de camp and went on to write "Shane" and "A Place in the Sun," two of my favorite movies. I never got to have those conversations.

"I was a young teenager with a bit of hero worship for Warren Beatty and Paul Schrader and all these people that I would eventually know as an adult years later."

As I got older, and my aunt and uncle inherited the next generation of filmmakers, I was interested in entering the business and being an actor. So the people that came to their house, the screenwriters and the filmmakers, I was precocious enough and curious enough to know what they did and asked them all sorts of questions. I was in awe of them. I was a young teenager with a bit of hero worship for Warren Beatty and Paul Schrader and all these people that I would eventually know as an adult years later. So, when it came time to write the book, I fully embraced where I came from.

Of the many themes in the book, one that jumped out at me was secrecy. You referred to your mother having lived in a 'house of lies' with your father and that secrets were a 'Dunne family tradition.' Do you think you could have written this book and shared all that you did if your parents, uncle and aunt were still alive?

Yeah, I do. I would have been a little daunted by it, but I think they'd be happy with the final product. John and Joan were writers who would write about their own marriage problems and whether they should divorce or not. And my father, when my brother was in a dark place emotionally, would say, 'You know what, Alex? Write it down. Say whatever you want about me. I don't care. Just use your voice. Write it.' When it came time to writing this book, I couldn't begin without my brother's acceptance. So I asked him, and he said, 'I don't care what you write about me. Just have it come from a place of love.'

And that was the perfect note for everything that I wrote about. Because I knew while I was talking about difficult periods — infidelities and closeted behavior and drinking and toxic relationships — I knew where they ended up. I knew there was going to be a resolution. I knew what an incredible man my father was going to grow to become, and that my father and John would reconcile a year before he died. All three of them were journalists and they often wrote in the first person, so I think they would have looked at it not just as their relative writing about them, but as a writer writing about them.

You write about your career from going from theater in New York to Hollywood films. What roles or projects have brought you the most joy? What are you proudest of in your career?

Just about everything that I've directed I'm proud of. My partner, Amy Robinson and I, produced movies with some of the greatest filmmakers — Sidney Lumet, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, Lasse Hallström. But if I had to boil it down, what I would say I'm most proud of is that I was able to make a documentary ("Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold") about my aunt, have her see it while she was alive, and get one of the longest standing ovations they've ever had at Alice Tully Hall at the New York Film Festival, holding her up at the balcony and watching this love come showering up toward her from the crowd below. On a personal and professional level, it hits both bases for me. I'm very proud of how I made it and I'm very proud that I was able to introduce a much larger audience, a younger audience, to Joan. They had to reissue all her books as a result. And the look on her face, it still gets me.

"What I would say I'm most proud of is that I was able to make a documentary about my aunt, have her see it while she was alive, and get one of the longest standing ovations they've ever had at Alice Tully Hall at the New York Film Festival."

When I showed her a rough cut on a little laptop, I said, 'I'll stop for a bathroom break.' By this time, she was in a wheelchair, mid-period in her Parkinson's. I said, 'You want a bathroom break?' And she goes, 'Keep going, keep going, keep going!' I hit the bar to get it going and then it ended, and she looked at me, her eyes welled, and she just said, 'Thank you.' That was definitely the most rewarding moment I've had about anything I've ever done.

You also write quite a bit about Carrie Fisher and your years-long friendship. Looking back, what influence did she have on your life?

My sense of humor. We were rarely serious. We would talk to each other in musicals and made-up musicals about anything from [sings], 'I'm off to the bathroom! I'll call you right back and if I don't come out soon, come and get me!' We would sing all the time. And we laughed like crazy. When writing that section I channeled her. Her voice was so clear in my head. Friends I grew up with, and later friends of Carrie, all read that and went, 'Oh, my God, you got her. You got her.' I was laughing out loud, typing it.

One of the things I love about the book is the dialogue. You have these moments of great banter with people like your sister or Carrie. You do a great job of really pulling the reader in and making it feel as though we're there with you. How was it for you to relive these intimate moments?

I loved it. I mean, the voices just came so clearly in my head. At my desk, I have a punch board and there are pictures of my family members, and I would look at different people who ended up being in the book and they were so present that the pictures themselves look different to me. I noticed things I'd never noticed before in the pictures. They had a shimmer about them. I found myself sadder to finish the book, to not have those voices anymore, than to write some of the saddest sections of the book. There was a little bit of mourning going on.

The first half of the book ends with your sister's murder. Obviously, an incident like that is going to change everyone involved, but in this case it did it in unexpected ways. Your father's writing career was reignited; your mother found a new community in victims' rights advocacy. Were there ways that it affected you that were similarly unexpected?

I think my relationships with women completely changed. I mean, I was never abusive in any way, but I became very, very sensitive with — having seen my sister's reputation be dragged through [the mud] — blaming the victim. Whenever I read about a sensational murder, I think about the person who was killed and what their reaction would be to reading this. One of the things I'm most proud of about my dad's reporting is that if he wrote about someone like Phil Spector, he would make sure that Lana Clarkson [the victim] was treated as a human being and not a third-rate actress, as she was called continuously over and over and over.

"I've always been outraged about guns, even before Dominique was murdered, but I definitely felt the need, like my parents, to throw myself into a cause where innocents were being pointlessly murdered."

At the same time, I also hate the abuse of the word assault, which I take very literally, both sexual and physical assault. Sometimes when I hear the word used, and it was about a guy who patted an ass or something — you know, there's another way to rephrase that than diminishing an assault that will alter and traumatize your life.

My parents had the victims' rights thing covered; I was drawn towards the gun control movement. I've been involved with that through Brady and I've done PSAs that I've directed. I've become very close with families in Sandy Hook and from the Aurora massacre. Francine and David Wheeler, whose child was killed in Sandy Hook, and Sandy and Lonnie Phillips, whose daughter was murdered [in Aurora], talk to me because we have the same dog whistle. They know I understand. That has brought us very close.

One of the projects we're doing is something that Francine Wheeler has written. She was an actress and has written this beautiful play called "Just Five Minutes," which I helped bring in actors to do. So, I'm using whatever connections I have creatively and whatever support I can give emotionally to families like that. I've always been outraged about guns, even before Dominique was murdered, but I definitely felt the need, like my parents, to throw myself into a cause where innocents were being pointlessly murdered.

The book ends in 1990, upon the birth of your daughter. Why end there?

Because I looked down at the page count and I was on, like, 300 pages and I was still 13 years old. [Laughs] I wasn't sure how it was going to end. All the way through I had no idea when it would end in my life. But at one point when I was almost three quarters full, I thought of a prologue that sets this whole thing off, when the detective comes to my mother's house in the middle of the night to tell her about Dominique.

And I felt Dominique all the way through it. I mean, that was the drive all the way through, all the way through, all the way through. Subconsciously, consciously, I felt her on every page. And I'll never forget that moment, that feeling of being alone with [my daughter] Hannah who was 10 minutes old and feeling my sister's presence. It just felt like an organic way to end it.

Read More