Predicting Who Will Be President

A new history of computer forecasting in national elections is a timely read as November approaches

As Election Day drew near, the news media was in crisis. Public trust in its ability to forecast and report presidential election results was at an all-time low. Four years earlier, the prognosticators, pollsters and reporters who covered the presidential election got it all wrong.

The year wasn't 2000 or 2016 or 2020 or 2024. Talk of hanging chads and fake news was a lifetime away. All of this electoral gloom and doom took place deep in the heart of the good old days: 1952.

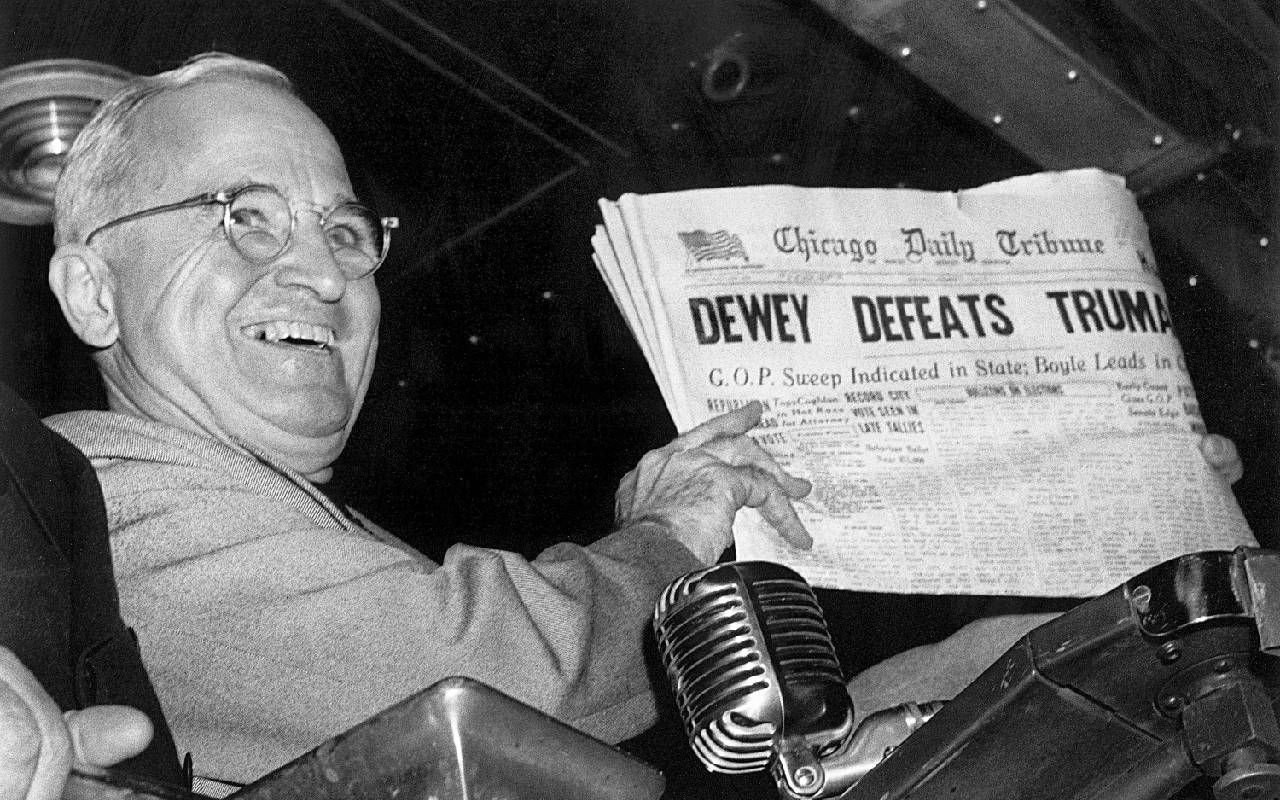

Print and broadcast journalists alike feared that the presidential race that year between Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson would be a repeat of 1948, when erroneous polls and political analyses resulted in the Chicago Daily Tribune's infamously inaccurate front-page banner headline: "Dewey Defeats Truman."

A Very Rocky Start

New York Governor Thomas Dewey had not, in fact, defeated President Harry Truman. Nor had Dewey's Republican Party won back control of the House of Representatives and the Senate, as many newspapers had forecasted.

The fear of a repeat of that abysmal Election Night performance led to a then-unlikely collaboration between two groups of pioneers in the inchoate electronic age: broadcast journalists and computer scientists.

"In the early '50s, it was not at all obvious that this was a thing that should be done."

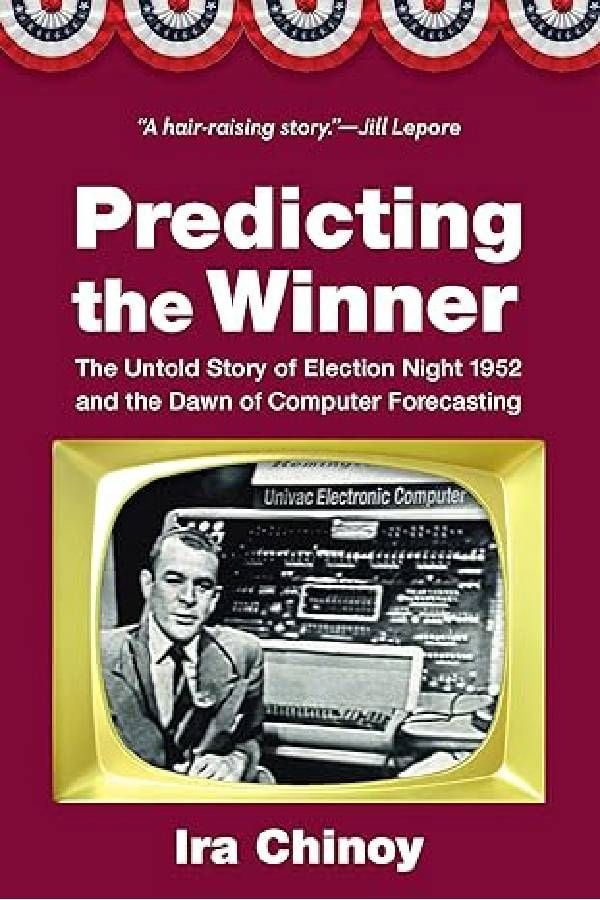

The application of machine technology to election returns in the 1952 race is the subject of a timely new book by the veteran journalist Ira Chinoy, "Predicting the Winner: The Untold Story of Election Night 1952 and the Dawn of Computer Forecasting."

On that Election Night seven decades ago, CBS used UNIVAC, the first successful civilian computer, to tabulate and project election results while NBC made use of the Monrobot, a machine created by the Monroe Calculating Machine Company of New Jersey.

"In the early '50s, it was not at all obvious that this was a thing that should be done," Chinoy said, noting that journalists had a long track record of successfully reading the electoral tea leaves before this newfangled application of machine technology.

"Editors knew how to make sense of returns from a particular precinct and get a sense of how the vote was going," he said, which was a product of the local knowledge and institutional memory that journalists developed working on hometown newspapers across the nation.

Doubting the Data

After "Dewey Defeats Truman," however, a marriage of convenience and simultaneous aloofness developed between the chattering and computing classes.

Lacking the confidence of later generations of technology entrepreneurs, computer scientists in the early 1950s balked on Election Night, withholding their final projections to the networks for fear that they got it wrong.

"When they saw this projection that it was going to be a landslide for Eisenhower, they thought it couldn't be right," Chinoy said. UNIVAC held back its findings, fearing that a mistake would set their project back for years to come.

After failing so catastrophically in 1948, the country's major pollsters were equivocal in presenting their findings in 1952. The major polling agencies (Gallup, Crossley and Roper) all presented it as a tossup and the computer scientists kept waiting for said tossup to materialize.

Instead, Eisenhower defeated Stevenson in a landslide, both in the electoral college and the popular vote. The computers knew it well in advance, but the people didn't have the nerve to present their findings.

Skeptics and Supporters

Many commentators took years to accept the viability of computer forecasting, including the likes of Edward R. Murrow and Eric Severeid, two of the most esteemed broadcast journalists of the era.

One outlier was CBS' Charles Collingwood, a dashing reporter who later became known for his White House tour with Jackie Kennedy. Collingwood saw the practical applications of machine technology to election projection as clearly as anyone.

He expressed a longstanding interest in the relationship between statistical analysis and politics. On election night, he presented the UNIVAC computing machine to the public. He leveled with viewers about what was happening, explaining that the use of computers for projections was an experiment on their part.

The Legacy of Big Tobacco

Over the next few election cycles, computers played a more significant role in projecting results. It was not until relatively recently that skepticism about the effectiveness of digital prognostications became more pronounced.

Chinoy suggests that this is part of a broader skepticism about institutions that has germinated in the American political culture in recent decades — a skepticism shaped in part by Big Tobacco's disinformation campaign in the late 20th century.

Tobacco companies being sued for knowingly selling addictive products that cause cancer waged a wide disinformation campaign that called into question the veracity of abundant scientific research demonstrating the harm done by smoking and chewing tobacco. Chinoy sees the current rhetoric around "fake news" and rigged elections as a legacy of Big Tobacco's campaign to undermine the credibility of legitimate research.

"It's not really about better math," Chinoy said. Projections are an imperfect but useful tool in reporting. "We've got to get to the bottom of this decline in trust in journalism and rise in news deserts."

News deserts refer to the growing number of communities that are not served by a local newspaper, which are historically the most trusted news source by the public.

According to a 2023 survey by Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, at least 204 counties in the United States have no local news source. Another 1,766 — fully half the counties in the United States — have only a weekly local news outlet.

Misinformation Fills a News Vacuum

Social media appears to be filling the news vacuum for many Americans, which has ramped up the quotient of misinformation in the public discourse.

"I think with, for example, Donald Trump saying 'it's rigged, it's rigged, it's rigged,' there's some theorizing that it may cause Trump voters to not go to the polls. 'Why should I bother if it's rigged.' And he's going to say he won anyway," Chinoy said.

"Predicting the Winner" was 20 years in the making. Chinoy came upon the topic while writing his doctoral dissertation. Before entering academia, he worked for decades as an investigative reporter for four newspapers, including the Providence Journal and the Washington Post.

Chinoy sees the current rhetoric around "fake news" and rigged elections as a legacy of Big Tobacco's campaign to undermine the credibility of legitimate research.

At both publications, he was a member of teams that won Pulitzer Prizes for their investigative reporting. Eventually, he became an instructor at the University of Maryland's journalism school while working on his Ph.D. in journalism studies at the institution.

"I was curious about why there was so much resistance to the computer as a tool in journalism for so long," he said of his dissertation topic. "I thought maybe I could explore how computers and journalism first hooked up. That's what got me to this 1952 election."

Chinoy's background as a journalist prepared him for the digging required of a historical researcher. He enjoyed the treasure hunt for archival materials and interviews with people who participated in that long-ago election night.

His research and writing skills are evident throughout the text. He is a first-class prose stylist who writes with the gravitas of a researcher who knows his subject inside and out.

"Really good historians and really good investigative reporters don't cherry pick their facts," Chinoy said. "They try to get the whole picture, and if something is at odds with their preconceived notion, they deal with that. I wasn't afraid of what I didn't know. My willingness to just pick up the phone and call an archivist really made the difference."

Context Will Be Key

As Election Night 2024 approaches, Chinoy believes context will be essential when figuring out what the immediate results mean.

"I am really looking for the quality of the comparative data that whoever is reporting on this is using. And also to their openness to all kinds of different ways of knowing," he said.

Chinoy notes that it's hard to know what's in people's heads but cites a broad consensus among election watchers that whichever candidate excels at getting out the vote this November will likely win the presidential race.