How Wheelchair Basketball Brought Paralyzed Veterans Into the Game

A new book highlights how this sport offers those with disabilities camaraderie and competition

World War II spurred countless historic and cultural developments. A recent book highlights one that's been lost to the march of time and justified pageantry: the creation of wheelchair basketball.

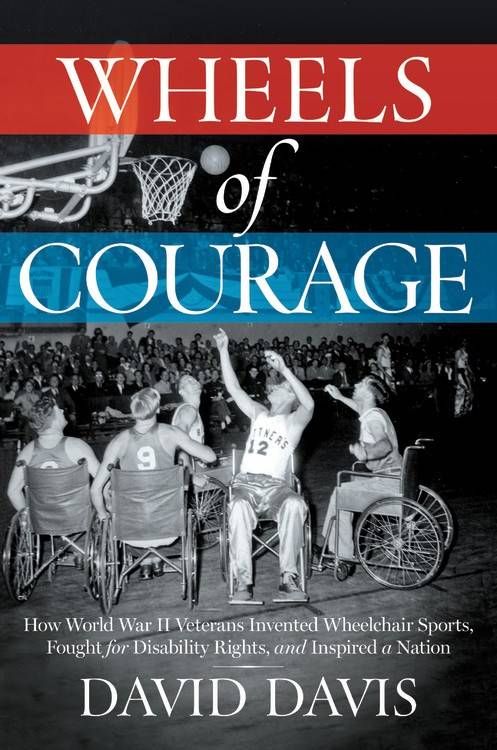

David Davis' "Wheels of Courage: How World War II Veterans Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation" chronicles the changes in medical treatment, perception and politics surrounding paraplegia from the mid-1940s to the early 1960s.

The author of "Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku" admits to a big learning curve with his latest effort, something he couldn't always atone for by scouring books and old newspaper articles.

For example, when interviewing a source, Davis used the term "wheelchair-bound" and immediately regretted it.

"We are not wheelchair-bound, we need a wheelchair to get around, but we get around," the man informed Davis, a veteran sportswriter.

"There's just so much ignorance about disability," Davis, 57, says. "Whether it's using language or just assuming they're paraplegic, they can't have kids, they can't have sex. It's a complex issue, and an individual one."

Wheelchair Basketball First Used for Rehabilitation

As Davis discovered in his research, before World War II, the ignorance surrounding the treatment of paraplegics was either fatal or unfeeling. Young men wounded on the battlefield were sent home to die or shuttled off to sedentary isolation in an institution or maybe the family home.

"There's just so much ignorance about disability."

A few developments prompted a dramatic reversal. Medical treatment improved vastly.

Dr. Donald Munro championed round-the-clock treatment of paraplegics that stressed vigilance and individualized, holistic care that involved specialists such as neurologists, dieticians and plastic surgeons.

That tack was embraced by Dr. Ernest Hermann Joseph Bors, a captain in the U.S. Army Corps who was selected by the Veterans Administration to lead the nation's first spinal-cord injury ward, Birmingham General Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif., which opened in 1945.

Munro also stressed that it was ultimately up to the patient to get better.

Enter Bob Rynearson at Birmingham General Hospital, who had the simple, ingenious idea to use basketball as part of the veterans' rehabilitation. The creation of the more maneuverable, lighter Everest & Jennings wheelchair made the game easier to play.

Most importantly, wheelchair basketball gave paralyzed veterans, the first generation to survive their affliction, "a sense of normalcy," says Davis, who lives in Los Angeles. These men would have recreation in their lives, even families and jobs. It would be different, "but it [was] going to be a full life."

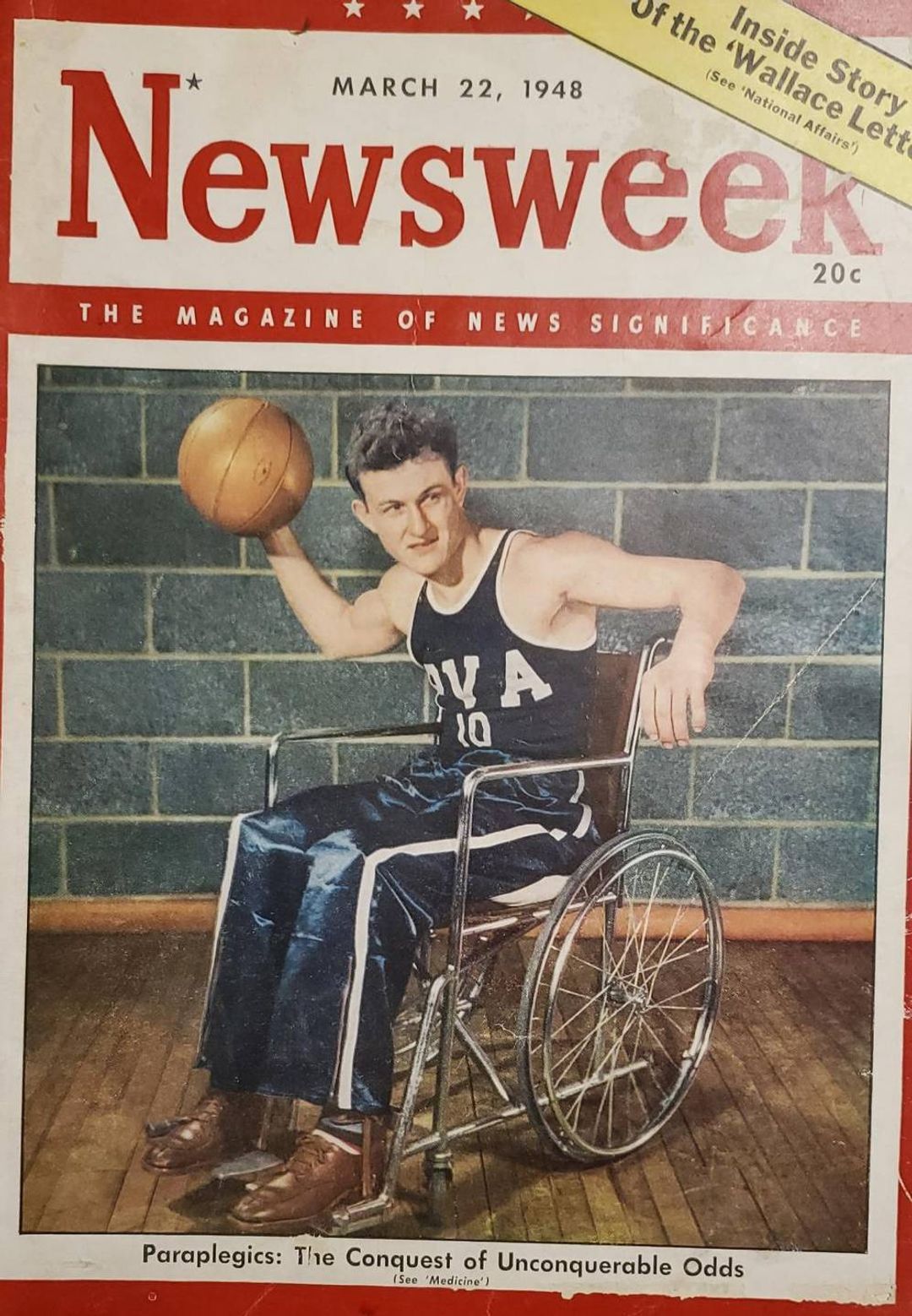

As wheelchair basketball extended beyond hospital gyms to the Flying Wheels squad "hooping it up" on nationwide tours, game attendees and newspaper readers had their notions of disabled Americans upended, Davis says. Here were men who were clearly athletic, not relegated to life's sidelines.

One noteworthy aspect of Davis' book is how the sport's rise mirrored progress in the paralyzed community, whether it was veterans being granted money by Congress for adaptive housing to the creation of the Paralympics.

"The presence of the paralyzed veterans on the basketball court, and their demands for much-needed benefits helped usher in a more enlightened era just as people with disabilities were beginning their arduous fight for equal rights," Davis writes.

'A Confidence Builder'

The impact of the game on its later participants has not diminished.

Jerry Allred, 61, of Hoover, Ala., played wheelchair basketball for 35 years. At first, he felt the sport was too slow with little contact. But he eventually fell in love with it — even after he broke his right hip during a game.

Hey, Allred thought, this is a sport.

"Meanwhile, you have to maneuver the chair left-right, back and forth, play defense...It takes a lot of coordination."

Allred, the victim of a car accident initiated by a drunk driver, was permanently paralyzed in December 1976, his senior year of high school. He was playing wheelchair basketball a year later. On the court were Vietnam veterans and men who had careers and families. It didn't matter to the 18-year-old.

"There was camaraderie with them," says Allred, a retired computer programmer. "I learned from them. It taught me that there was a spiritual part; I could do this."

The game was a "confidence-builder in everyday life," he adds.

Now a youth coach, Allred imparts that lesson to his teenage players: "You can live a productive, independent life and be happy," he says.

In fact, opportunity has increased as the game's status has improved: A player Allred coached received a partial scholarship to play wheelchair basketball at the University of Alabama.

It is a skill sport, says Allred. Davis concurs.

As part of his research, Davis played wheelchair basketball and "could not believe how difficult it was." Running up and down the court is a key component to playing basketball, but the legs provide the power for an ambulatory player to shoot the ball. Sitting down, Davis felt like a 6-year-old shooting on a regulation 10-foot-high hoop.

"Meanwhile, you have to maneuver the chair left-right, back and forth, play defense," he explains. "It takes a lot of coordination. For someone like you or me, quote-unquote normal people, that adjustment is very, very difficult."

Wherever there's a hoop, though, there's a little bit of hope.

The spiritual lift that young veterans (and trailblazing players) such as Stan Den Adel, Gene Fesenmeyer, and Johnny Winterholler received on the basketball court has not changed in more than 70 years.

Allred says few activities are more enjoyable than playing two-on-two. And though his playing days are behind him, Allred can still go to the court, take a shot and fall in love all over again.